Crafting the Future of Education: Building the Khan Academy Lab School

After a decade of teaching in the Washington DC area, national recognition, and advocacy for education reform, I found myself at a crossroads. The culmination of a three-year salary freeze and futile attempts to secure adequate funding for our school pushed me to make a bold decision – quitting my teaching job without a clear path forward. I made the announcement during an interview on ‘This American Life’ and my pivotal moment caught the attention of Sal Khan, the visionary behind Khan Academy, an online education platform. Fueled by an NPR listener’s persistent emails, Sal and I eventually met and engaged in conversations that would eventually lead to the birth of the Khan Lab School. As the first hire, my role was not only to recruit a team and design a school that addressed the failures of public education but also to navigate the constraints of a budget comparable to the median spending per student in the nation.

During the inaugural year of the Khan Academy Lab School, I had the privilege of helping shape a pioneering approach to education, one that reimagined the role of both teachers and students in the learning process. At the core of this vision was the independence model, which centered on empowering students and their families to take ownership of their educational journey while ensuring alignment with state standards. The independence model replaced the traditional teacher-led, one-size-fits-all approach with a dynamic, personalized framework. Instead of the teacher acting solely as a content provider, they became curators of the student’s educational experience—mentors who guided, inspired, and opened new doors to knowledge and skills.

Sal Khan was deeply invested in the concept of mastery-based learning, which was a core principle of the Khan Academy platform. He was eager to see how the data and insights gathered from the online platform, along with research findings, could be applied in a real-world school setting. At KLS, mastery-based learning followed the same philosophy as the online platform—students had to consistently demonstrate their understanding by achieving ten correct answers in a row before progressing to the next concept, particularly in math. By shifting these drill-and-practice exercises to independent study, teachers were able to move away from traditional grading methods and instead focus on portfolio-based assessments. This approach emphasized students’ ability to apply their knowledge in meaningful ways, rather than simply preparing for standardized tests.

The independence model we were experimenting with invited students and parents to actively participate in the planning process, transforming conferences into a collaborative effort. Families could co-design their child’s learning journey by selecting from curated playlists, setting goals, and working with teachers to create a balanced and enriching experience. As a community, we collaborated to organize school-wide and small group projects into personalized playlists, ensuring they aligned with the logistics and objectives of KLS. This approach allowed teachers to effectively meet the educational needs of classroom-sized groups of 24 or more students while maintaining weekly face-to-face meetings to build relationships. At the same time, many routine “housekeeping” tasks that typically consumed teacher time were delegated to students, fostering their sense of ownership, pride, and real-world problem-solving skills.

For me as a teacher, this approach was transformative. Instead of spending endless hours preparing lectures or grading worksheets, I could focus on building relationships with students, understanding their interests, strengths, and aspirations. It meant that I could spend more time facilitating meaningful discussions and guiding students through complex ideas and challenges. I had more time to plan for connecting students with cutting-edge tools, technology, and community experts.

The first year witnessed projects like “Racetrack Day,” where students designed and constructed wooden cars for a box car race track on Google’s campus. “Dinner Theater” followed, featuring students growing, cooking, and serving food for 100 at a pop-up dinner theater. The school’s emphasis on hands-on, real-world projects culminated in a camping trip where students took the lead in teaching each other and their teachers about their passions.

The first year witnessed projects like “Racetrack Day,” where students designed and constructed wooden cars for a box car race track on Google’s campus. “Dinner Theater” followed, featuring students growing, cooking, and serving food for 100 at a pop-up dinner theater. The school’s emphasis on hands-on, real-world projects culminated in a camping trip where students took the lead in teaching each other and their teachers about their passions.

My tenure at the Khan Lab School was a testament to the transformative power of reimagining education. The freedom to innovate, the emphasis on real-world applications, and the collaborative approach to design marked a departure from the conventional, bringing joy and authenticity back to the classroom. This venture taught me valuable lessons about the potential for radical change in education and the importance of pushing the boundaries to craft a future where every student thrives.

However, in navigating the uncharted waters of education reform, the Khan Academy Lab School project brought forth challenges that forced us to confront deep-rooted perceptions about traditional education. Collaborating with progressive leaders, parents, and stakeholders, the initial enthusiasm to revolutionize every aspect of conventional education often transformed into a complex web of conflicting sentiments.

Progressive parents in every private school I have worked or partnered with, while initially vocal about discarding traditional elements like blackboards and classrooms, gradually become uneasy as the new educational experiences unfold. Their concerns reveal the delicate balance required when implementing change – a balance I explored through interactions with innovative school designers Larry Rosenstock and Jeff Sanderfer.

During insightful visits to High Tech High and Acton Academy, Rosenstock and Sanderfer emphasized the importance of shielding the design process from conflicts of interest and skepticism from stakeholders. Larry advocated for removing parents from the board and staff, citing their potential conflicts, while Jeff maintained a strict policy against parental involvement in the design or function of the system. The struggle to reconcile these perspectives with my belief in the value of parental input proved complex. Despite spending extensive time building relationships with families, the challenge lay in finding ways to communicate and steward evolving ideas to critical stakeholders effectively. In hindsight, I recognize the need for constant prototyping and visual aids to bridge the gap between visionary concepts and stakeholder buy-in and understanding.

Beyond the tension between designing a radically new school and preserving proven practices, the endeavor exposed the difficulty of effecting change in established educational systems. Hiring experienced teachers proved challenging, as many were resistant to altering grading practices and behavior strategies. Even attempts to recruit innovative, award-winning teachers yielded responses of appreciation but declined offers.

Moreover, the landscape of progressive education practices, spurred by national initiatives like “No Child Left Behind,” faced scrutiny. Some practices, initially supported by data, succumbed to pressures from profit-driven products, inadequate training, and a lack of educator support. As a result, adopting new ideas or discarding old ones became an intimidating prospect.

Despite these challenges, the Khan Academy Lab School embodied its “lab” moniker, acknowledging the discomfort of working in an active petri dish while tirelessly striving for innovative solutions. Lessons learned underscored the importance of balancing the pursuit of groundbreaking ideas with the need for stakeholder engagement, effective communication, and a nuanced understanding of the intricate dynamics within the realm of education reform.

Designing the Khan Academy Lab School

Philosophy

In shaping the educational philosophy and curriculum of the Khan Academy Lab School, we drew inspiration from a blend of innovative educational ideologies, each contributing to the school’s unique approach to learning. Sal Khan’s book, “The One World Schoolhouse,” served as a foundational guide, advocating for methodologies such as the flipped classroom, mixed-age learning environments, and a mastery-based approach where students simply needed to demonstrate proficiency to progress.

In shaping the educational philosophy and curriculum of the Khan Academy Lab School, we drew inspiration from a blend of innovative educational ideologies, each contributing to the school’s unique approach to learning. Sal Khan’s book, “The One World Schoolhouse,” served as a foundational guide, advocating for methodologies such as the flipped classroom, mixed-age learning environments, and a mastery-based approach where students simply needed to demonstrate proficiency to progress.

A crucial element of our design was the implementation of the flipped classroom model, allowing students to engage with instructional content at their own pace outside of traditional class time. This not only catered to individual learning styles but also facilitated more personalized interactions during in-person sessions.

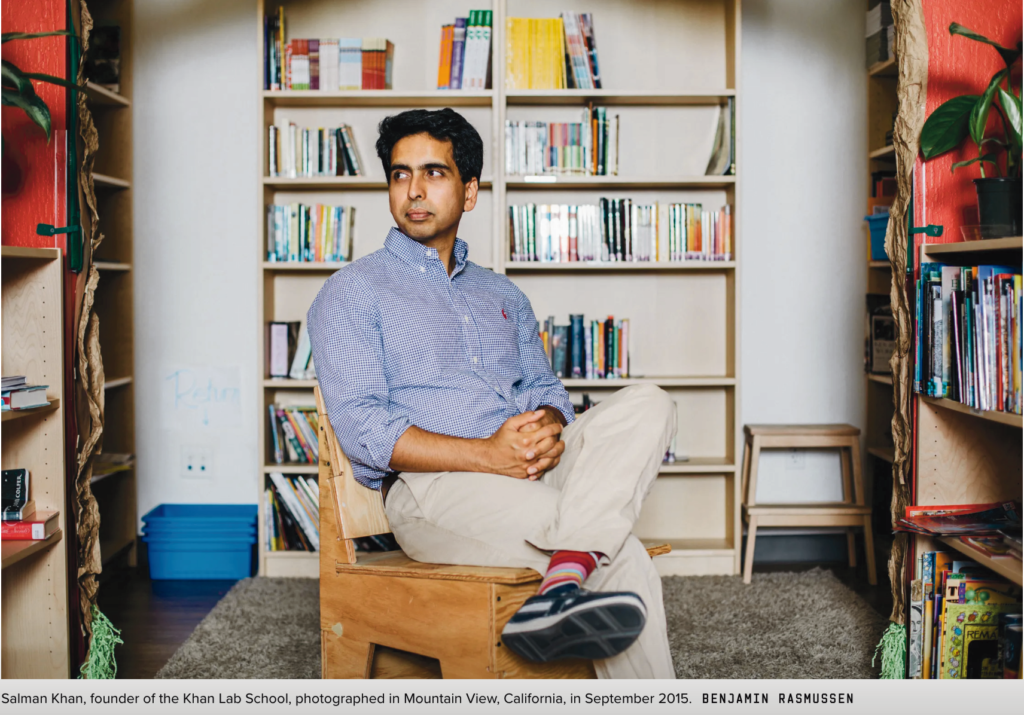

Originally published in Wired magazine Oct 26, 2015

Sal Khan’s vision, as articulated in his book, emphasized the importance of leveraging technology to enable teachers to access real-time data on student progress through its mastery based practice system. The Khan Academy platform, provides teachers with instantaneous insights and allowing for the dynamic formation of flexible student groupings on the fly. Investigating this approach and its potential would for the basis for the first half of each day.

My collaboration with Larry Rosenstock, the founder of High Tech High, introduced key concepts that enriched the school’s original design philosophy. The adoption of student-operated playlists with individualized tracks of study curated by both teachers and students became a cornerstone. The Khan Academy team had also collaborated with area independant high schools who were using the playlist concept successfully allowing my team and I additional observations and strategies for implementing this approach.

Rosenstock’s emphasis on utilizing real-world audiences in assessments and fostering a deep trust in students aligned seamlessly with my vision, and led to the creation of public exhibitions as a goal for each of our semester long school-wide projects. I had led events and published an article on the value I held in my experiences with inviting the public to celebrate learning in schools, so I was excited to learn more from Larry and see how far this strategy could elevate student learning. This authenticity in evaluating learning formed the basis of collaboration in the school community, empowering students to actively participate in shaping their learning experiences with their teachers.

My background in the DC public school system brought forth valuable elements, including a focus on community events, outdoor education, bi-weekly walking field trips to various city resources, and the integration of student-led design into the learning process. These components, proven successful in my prior award-winning career, drove my input into the educational design philosophies at Khan Lab School.

Combining these diverse elements was an exhilarating challenge. We were fortunate to have the support of stakeholders who embraced this amalgamation of philosophies, creating an environment where our innovative ideas could flourish. The enthusiastic participation of our incredible students added an extra layer of excitement to this educational experiment, making the realization of our shared vision all the more rewarding.

Hiring and Training the Team

Embarking on the task of building the Khan Academy Lab School team, I drew inspiration from Google’s hiring philosophy, emphasizing the importance of finding individuals who aligned with the innovative vision. Google’s emphasis on cultural fit resonated with the unique challenges and aspirations of our project. Leveraging my networks within Khan Academy and Google, I began spreading the word and soliciting recommendations for educators ready to embrace the difficulties of creating something entirely new.

The recruitment process involved a series of interviews that allowed both parties to understand and align with the project’s ethos. I sought educators eager to jump into the unknown, ready to face the challenges of crafting a more effective learning system. Performance tasks became a key element in the interview rounds, requiring candidates to respond to creative prompts or immerse themselves in a day at the Khan Lab School. This approach aimed to identify individuals whose passion for creativity and a desire to contribute to transformative education were palpable. It was essential for candidates to experience firsthand the non-traditional nature of our school and confirm their commitment to the demanding yet rewarding journey of designing and teaching simultaneously.

Recognizing the significance of adopting new grading practices and behavior strategies, I facilitated enriching professional development opportunities for our teachers. Drawing from my experiences, I organized visits to High Tech High in San Diego, CA and Acton Academy in Austin TX, collaborating with staff at these institutions to explore effective learning strategies. These visits were not merely about acquiring new skills but empowering our teachers to see themselves as designers with meaningful input into our program’s evolution.

The freedom to create personalized learning experiences for students came with the challenge of managing an uncharted system. Patience and tenacity were identified as critical virtues to avoid teacher burnout. By immersing the team in the mindset of change at High Tech High, we aimed to instill a deep understanding of the transformative journey they were undertaking. These experiences were not just about learning practices but fostering a culture of adaptability and continuous improvement. Through these intentional efforts, our educators were not only equipped with new methodologies but also empowered to contribute actively to the ongoing evolution of the Khan Academy Lab School.

Parental Involvement and Communication at Khan Academy Lab School

The project’s first board was actually Khan Academy’s board at the time of the projects inception. Which was an amazing group of leaders to learn from, every moment I spent in the room with them I was a student myself. Their role was authorizing Sal to create the Khan Academy adjacent project, an in-house lab school. Once Khan Lab School was approved unanimously by the KA board, Sal brought on a board made up of parent volunteers with specific skill sets that each could help get the project up and running quickly, at world class quality and at the speed needed to meet our timelines. I spoke with HTH designer and founder and my then mentor, Larry Rosenstock about my fears of conflicted interests and how to ensure I was managing and communicating with board, parents and the overlap. Larry highlighted the importance of avoiding the conflict of interest and wisely encouraged me to strategize for a quick roll-off for parents who were serving on the board. Sal had recruited parent support an the incredibly low cost of free to quickly set up the school (with world class resources) and each member intended to roll off once their roles on the board focusing on their particular connection to their skillset and roll off after the task was done. As Larry advised, relationships and communication were key in collaborating with they key stakeholders through a fast-paced start up and each of us holding many mission critical roles. We developed systems to collaborate, creating regular workshops and evening sessions with parents through our first year. We would be introducing and test ideas that had never been seen, or somthing we saw over at Brighworks or Acton Academy and wanted to test with kids highly involved in the experiments. It would not be easy for everyone to understand nor would gaining consesus be possible without deep relationships and trust.

Navigating Revolutionary Change

Revolutionizing traditional education required a thoughtful approach to parental involvement and communication. In the early stages, Sal Khan recruited an initial group of parents through the Khan Academy network, seeking both financial support for the project and those aligned with the unique program’s focus on practice and skills, along with a dedication to performance and synthesis of learning across domains. The goal was not only to gather support but to create a diverse community that could provide valuable insights for designing a system applicable to public schools.

To ensure a diverse participant pool, I engaged with each family multiple times, emphasizing our experimental and rapidly evolving approach. The focus was on introducing the program rather than evaluating students or parents based on their abilities or achievements. While some families were drawn to the project’s experimental nature, others sought prestige for their child’s college applications.

The original plan was a balance between tuition-paying and scholarship-funded families, in an attempt to better mirror the social dynamics of public schools. The excitement of a new school design taking place on Google’s campus attracted an overwhelming interest from Bay Area tech parents seeking a unique educational experience for their children. However, it became clear that not every family was ready to embrace the experimental nature of our program. Not everyone was a good fit for the pilot year and there were, of course, modifications and dropouts after the first year.

Monthly meetings with parents became a crucial element in keeping them informed about changes and the outcomes of our various experiments. These sessions served as platforms for open discussions, allowing parents to voice concerns or suggestions. However, to prevent these meetings from devolving into grounds for complaints, I underscored the importance of prioritizing relationships and positive experiences in our communication formats. To foster more casual interactions between parents and the team, we introduced post-meeting dinners at nearby restaurants. This informal setting encouraged a more relaxed and collaborative atmosphere, reinforcing the idea that the relationship between parents and the school was a partnership.

While the experimental nature of the Khan Academy Lab School wasn’t a perfect fit for every parent, the ongoing communication channels ensured transparency and facilitated a sense of community. This continuous dialogue was essential in navigating the complexities of parental involvement and sustaining support for the revolutionary educational model.

Collaborative Design Process (no, really)

My deepest hope and greatest drive at Khan Lab School was to authentically involve students in the process of designing their own learning experience and designing their own school. I believed in this idea coming out of my Washington DC classrooms where I tried to enthusiastically support every imaginative student idea and encourage students to think bigger and bigger. From student run and planned school dances and events to field trips, I collaborated with students and parents in creating big fun experiences in learning that were driven by student’s imagination and drive for discovery and responsibility. I wanted to bring this to the forefront of the Lab School’s design. It would be messy, especially in figuring things out as quickly as we needed to, but with systems and good communication, we drove that dream into reality together. Students were incredibly driven and connected to their learning directly proportional to their involvement in taking on leadership and responsibility in the design of the lab school. Students chose furniture, designated room useage, collaborated on schedule, and chose the topics for their learning during four daily whole group and small group meetings.

I studied systems like this that High Tech Elementary, Acton Academy and Brightworks teachers used to get the results that I saw during our embedded visits. Students as those schools, as such young ages, took on such enthusiasm for learning, and when asked why each and every one responded with some version of , ‘ because we get to do whatever we want.’ I was observing highly structured, well regulated, well managed classroom behavior and learning, and the kids were consistently telling me that they had unlimited freedom and that it was bliss. And I understood. I had spent ten years in my DC classrooms encouraging students to learn the habits of business and applied learning by empowering them to arrange their own field trips, including making calls to key stakeholders from the classroom and on speakerphone with support from peers and myself. Something changes when a student has been trusted with an adult responsibility by their teacher. I think it may be intangible and hard to describe for some students especially those that are earlier learners.

Mixed-Age Groupings

The concept of mixed-age groupings at Khan Lab School stemmed from Sal’s One World Schoolhouse, and it was a concept I was eager to explore and integrate into our educational approach. Inspired by our observations at Acton Academy and at Brightworks SF during the design and training phases of the KLS project, we were impressed by the maturity and responsibility that students developed in working with and mentoring younger peers.

We structured age bands as the foundation for groups of students, managed by the same teacher. These bands were based more on child development stages than strict age divisions, allowing for a nuanced approach to educational needs and group to group movement. We aimed to blend activities so that students on the younger end of a cohort had opportunities to lead and mentor younger peers, creating a dynamic and engaging learning environment. The age bands evolved organically, with younger cohorts having narrower developmental expectations, gradually widening for older cohorts. This intricate dance allowed us to balance the diverse needs of students through their developmental stages.

As a teacher with experience in a dedicated science lab and outdoor program for 700 pre-K to 6th graders, I felt comfortable navigating the educational code-switching required to accommodate varying developmental stages. Though challenging, it provided a unique opportunity to understand the intricacies of mixed-age groupings, a practice I firmly believe in for meeting the diverse needs of students seeking independence. I feel certain that this strategy requires training and experience in order for teachers to feel bought in, comfortable efficient and successful.

Schedule

Our prototype approach divided the day into distinct parts. Mornings were dedicated to small group and independent learning practice in core subjects like math, science, English language arts, and history. Afternoons were a canvas for creativity, with students embarking on collaborative large-scale, semester-long projects that responded to community-crafted prompts.

The ultimate design of the school itself was also a collaborative effort with students, involving them in mapping out the space and experimenting with room configurations. By gaining the power to decide upon the use of a classroom space, students more naturally and inherently took responsibility for creating organizational systems for materials and for keeping spaces clean and tidy. (Although it took time for this natural consequence to emerge!)

Playlists

Playlists were self directed learning activities that students could work on at their own pace during designated playlist work time. Student parents and teachers worked together to curate the list. Parents would provide their big goals and reasoning for their child’s learning during parent led conferences. Students would respond and the teacher helps to curate activities into projects that fit the community chosen big themes of the term as well as their personal interests. I observed these systems in use at several Bay Area schools. Most were interested in experimenting with ed tech to bring more independence and enthusiasm into student learning. It took time to develop a system, but I loved it and I believe students found their learning immensely satisfying.

A key component of the playlists is a flexible and tailored approach to curriculum design. Playlists allowed students and parents to choose from a curated menu of lessons, activities, and resources that aligned with state standards while being deeply engaging and relevant to the students’ interests. Or suggest their own. These playlists could include:

- Core academic content in math, science, language arts, and history.

- Hands-on projects that integrated multiple subjects, fostering creativity and critical thinking.

- Independent study opportunities, where students could explore topics they were passionate about, such as coding, art, or social justice.

- School-wide or small group experiential learning activities, like field trips, collaborative group work, and real-world problem-solving tasks. The oldest students at Khan Lab School walked to the Mountain View library once a week and even this simple act of being out in the world regularly, gave us many opportunities to inspire projects or lerning experiences.

Community Meetings

At the heart of KLS were two daily student-led whole-school community meetings that shaped the outline of the daily schedule and drove student led learning. The first meeting initiated the day with music, meditation, breakfast, and positive vibes, setting the tone for the school-wide project’s current status. This brief but impactful gathering also kicked off the daily cohort community meetings that preceded academic studies in the morning.

The daily experience was captured by our oldest student Malaina Kapoor then 12 (and now an accomplished writer and Stanford student. Her account of a day at KLS can be read here. She says, “We all, from the youngest kindergartner to the oldest middle schooler, decide our schedule and term goals, and help shape the new school with our ideas.”

Her description of the morning meeting illustrates the power of mixed age learning and student responsibility. She writes, “Every day the KLS community gets together to say good morning and get energized. My five-year-old friend Mylan slipped her hand into mine as we all turned to the student leader of the meeting, Isabella. This morning our greeting and energizer were blended into one—the snowball greeting. As a basket came around, I reached my hand in and drew out a crumpled-up piece of paper. Then, for one minute, we had a “snowball” fight. When time was up, the loud laughter ceased and everyone picked up a snowball, uncrumpled it, and went to shake hands with the person whose name was on their paper.”

Cohort community meetings empowered students with a democratic voice in the classroom, fostering responsibility and engagement. Student-led with a templated format, these meetings allowed every student an opportunity to share, respond, and address issues important to them. These meetings created a sense of investment in students’ educational experiences, keeping them motivated and engaged.

Afternoon meetings followed a similar structure, occurring after lunch and recess. These gatherings served as a platform to discuss cohort needs for the afternoon, aligning with the school-wide quarter-long project. The meeting format, though seemingly routine, required considerable training for students to lead effectively and for teachers to guide the process smoothly. The investment in teacher training was crucial to ensuring a successful implementation of this strategy, reflecting the broader ethos of KLS in student-centered and community-driven learning experiences.

YEAR 1: School-wide Projects

Each term of the first year of the Khan Lab school was driven by a school wide project attached to driving questions or challenges: ‘Who Are We?’, ‘Can a School be ANYTHING we want it to be?’, ‘Carnival of Caring for the Bay’ and ‘Students Create School.’

(Quarter 1): Prompt – Who Are We? – Students chose to create a “Racetrack Day”

The inaugural quarter project, “Who Are We,” marked the beginning of a journey into hands-on, collaborative learning. Embracing the spirit of a well known inquiry-based project, the prompt challenged students to explore and represent aspects of their lives through collected data. Each student selected several categories of personal interest, posing questions like: How many goal kicks do I practice each week? How tall am I? Any question that could yield data became a canvas for self-exploration.

The open lab space became a hub for students to visually represent their collected data, fostering a deeper understanding of themselves and cultivating habits essential for independent learning. As a community, we delved into personal insights, student-led small groups and collaborative decision-making through class meetings, addressing meaningful issues within the school.

Drawing inspiration from educational visionaries like Larry Rosenstock and Joshua Rothhaas, co-founder of project Ember, the project took an ambitious turn towards large-scale building. With a keen interest in empowering students through meaningful work and hands-on experiences with real power tools, the aim was to instill excitement and responsibility in their educational pursuits. Collaborating with design assistant Alejandro Poler, we crafted innovative furniture and re-buildable wooden parts, allowing students to create their own desks or prototype imaginative ideas.

Amidst the tinkering with our space and the exploration of self, the focus shifted to the immediate surroundings, asking crucial questions: Who are we as a group, and how do we learn best together? In collaboration with Joshua Rothhaas and his team, we embarked on a journey of collaborative design sessions with students, culminating in the goal of designing a public exhibition—a response to the question, “Who Are We?”

The brainstorming sessions sparked the idea of “Racetrack Day,” an event where students would showcase their math,

language, art, science, engineering, and technology learning. Curated by teachers, these learnings were transformed into small team-built box cars and grade-level projects. Younger students engaged in track design planning, testing lengths, and crafting wooden ramps. Middle-aged students focused on promotional media, writing, drawing, and recording messages, while older students coordinated the project and designed safe bleachers for audiences.

This transformative experience, blending academic disciplines with practical application, demonstrated the potential of project-based learning in fostering a holistic educational journey. The collaboration with Joshua Rothhaas solidified the belief that education could be an immersive and dynamic exploration, inspiring students to apply their skills in real-world contexts. “Racetrack Day” not only showcased their achievements but also laid the foundation for a year of innovative and student-driven projects at the Khan Academy Lab School.

(Quarter 2): Prompt – Can a School be Anything We Want It To Be? – Students chose to create a “Pop-Up Dinner Theater”

The second quarter embarked on an ambitious project eventually led by a challenge to create a “Pop-Up Dinner Theater” for 100 guests on a Google campus for one night. Guided by the principle of empowering students to shape their educational journey, I sought to lead the team in a direction where students would truly embrace their roles as architects of their learning experiences. Drawing inspiration from Joshua Rothhaas and his notion of “detox,” we aimed to break away from traditional habits, fostering a belief that students could lead and own their learning experiences within our school.

Embracing the ethos of Acton Academy, Brightworks, and High Tech High, I set the stage for students to tackle significant questions. As a precursor to this transformative quarter, we began by exploring individual identities with the question “Who am I?” This evolved into a collective inquiry: “Who are we as a community?” To deepen this exploration and solidify our commitment to a model for public education, I aimed to evoke a sense of wonder and curiosity through inspiring questions about school design. I hoped to inspire students by sharing the reigns of the mission of the school with them – to design a new model for public education. And I believed that the individual project questions should be inspired by this shared collaboration and meaningful power to shape their environemnt.

To accomplish this, I encouraged students to have conversations at home and scour the internet and beyond for intriguing and positive ideas that caught their interest. Our search spanned innovative technologies, Broadway sensations like Hamilton, and even pop-up restaurants pairing innovative chefs with unique locations for a single night. Students delved into the core question— ‘can our learning truly stem from any experience we enjoy or wish to pursue?’

The idea of a pop-up restaurant gained traction among students during school community meetings. Students initially expressed interest in helping the school to build its lunch program. Students asked questions about where food comes from, how it is prepared, how much it costs and the equity in our community of food availability. Student age bands sought early projects curated by teacher group leaders. Initially students chose to create a garden, a bakery and a vending machine to sell snacks grown in the garden (like sunflower seeds and dehydrated fruits). Allowing this investigation to grow in the community for a few weeks, we found our driving challenege, evolving into a large-scale project that encompassed a school-wide theater production and pop-up restaurant. We researched a San Francisco based organization that connected chefs with one night “pop-up” restaurants to promote creativity and social gathering around culinary art. Instead of reaching out myself, I prompted the older students to call via speakerphone to collectively pitch the concept to the pop-up organization. The pop-up team loved the idea, marking the beginning of a collaboration that would shape the rest of the quarter.

The interdisciplinary project involved multiple facets, including growing food, learning about soil and plant needs, and studying topics like photosynthesis. Older students curated mini-projects onto their playlists, covering everything from stage construction and lighting engineering to writing and composing music. Students who chose the play as their focus engaged in daily and weekly projects, contributing to the immersive experience.

On the night of the event, students showcased their culinary and artistic talents, serving dishes to 100 guests at a pop-up dinner theater on Google’s campus. The stage was a testament to their craftsmanship, featuring a musical written and performed by students. The entire school space transformed into a restaurant, stage, and gallery, showcasing a myriad of independent student projects, from garden plots and handcrafted vending machines to costume armor and a hovercraft.

This quarter was a pivotal moment, offering proof that education could be a dynamic, engaging, and successful endeavor. While we had much to figure out, it laid the foundation for our understanding of student learning and the culture we aimed to cultivate. My determination persisted—we were creating a model where teachers found fulfillment, parents had meaningful input, and students reveled in the joy of learning, setting the stage for a rewarding childhood experience.

(Quarter 3): Prompt – What are we concerned about? – students chose to create “Save the Bay Carnival” at a Google campus

In the third term at Khan Lab School, our design team decided to pivot, placing the reins of leadership firmly in the hands of our students. Eager to tap into their empathy and passions, the team initiated a school-wide exploration of student interests, uncovering a shared concern for the environment and a love for animals.

Teacher leaders orchestrated group sessions during community meetings, allowing students to express their thoughts and ideas. This collective brainstorming session became the foundation for our unique project—a day-long carnival fundraiser held at one of Google’s Mountain View campuses, aptly named the “Carnival of Caring.” The ultimate goal? Raising funds for Save the Bay, a non-profit organization dedicated to the stewardship of the San Francisco Bay watershed.

During this term, teachers and students worked in tandem to organize field trips to volunteer for Save the Bay. Older students took on mentorship roles, guiding their younger counterparts in various activities such as clearing brush and invasive plants from the watershed. These field trips not only aligned with our commitment to community service but also nurtured a sense of responsibility and cooperation among the diverse age bands.

The heart of the Carnival of Caring was the challenge posed to student small groups: create a carnival booth that blends entertainment with education, ensuring maximum engagement and replayability for visitors. To infuse academic depth into their projects, teachers carefully curated playlists incorporating Common Core and NGSS performance expectations, linking the students’ passion for animals with structured learning experiences.

The result was an inspiring convergence of fun and education. Students worked tirelessly during the day, researching, writing, reading, and designing physical structures, all driven by their love for animals. The space transformed into a gallery of animal study projects, a vibrant testament to their dedication and creativity. The Carnival of Caring not only raised funds for a noble cause but also exemplified the power of student-led initiatives, demonstrating the depth of learning that can emerge when driven by passion and purpose.

(Quarter 4): Prompt- We Built a School, Let’s Celebrate! – students chose to create a “Students Led a Day of School… in the Woods!”

As we approached the final term of our inaugural year at Khan Lab School, excitement bubbled over among our students and teachers. The quarter’s long-term challenge was inspired by the prospect of creating a booth for the 2015 Bay Area Maker Faire, following an unofficial field trip to the 2014 Maker Faire that left us buzzing with inspiration. In just a year, we had transformed our vision into something tangible and significant—a school we were proud to showcase.

The students, eager to commemorate their year of learning and collaborative school building, expressed a desire for a special celebration. Camping resonated with many of them, and the idea evolved into a family camping trip culminating in a promotion ceremony held in a bonfire-style gathering. Teacher designers skillfully curated the students’ interests and playlists, weaving them into cohort and individual projects, as well as a school-wide challenge: to recreate a day of school entirely orchestrated by students. Lessons, activities, and even the final ceremony would be led by the students, marking the pinnacle of their independence and collaborative efforts.

The event took place on a Thursday, inviting families to join for as much or as little of the camping trip as they could. A culmination of the students’ efforts, the ceremony was followed by a laid-back PJs day at school dedicated to reading and napping, giving everyone a chance to recover without encroaching on precious weekend time.

Throughout the day, students assumed the roles of teachers, guiding lessons on their favorite subjects and leading activities during PE time. The schedule mirrored a typical school day, with each segment filled by the students’ independent or group-led creations. The final ceremony, however, stole the spotlight, becoming one of the most poignant and heartwarming promotion ceremonies witnessed.

Students showered each other with congratulations, superlatives, and heartfelt letters, acknowledging and celebrating each other’s growth throughout the year. It was a touching and meaningful finale, highlighting not just the academic achievements but the bonds and camaraderie forged during the journey of building a school from the ground up. The camping trip turned out to be the perfect backdrop for this grand celebration, a testament to the unique spirit and community we had cultivated at Khan Lab School.

The journey of establishing the Khan Academy Lab School on Google’s campus brought forth unforeseen challenges that tested the resilience of the team. The high-profile nature of the venture attracted significant attention in Silicon Valley, a region notorious for its competitive and sometimes ruthless private school culture. Competitors in the ed tech space, driven by self-interest, occasionally resorted to unscrupulous actions, requiring a low-key approach initially to secure a stable setup and allow the team to acclimate to San Francisco.

Rapid growth emerged as a double-edged sword. While expansion was a testament to the project’s success, managing it proved a formidable task. Drawing inspiration from High Tech High and Google, I learned that preserving a positive culture amid rapid growth was as critical as managing the expansion itself. Unfortunately, the education system often neglects the value of nurturing a strong cultural foundation.

A surprising challenge arose from students’ disbelief in the innovative system they now had access to. The level of freedom granted surpassed their previous experiences, leading to skepticism about the sustainability of this unique approach. The “detox” period, as described by a colleague Joshua Rothhaas, highlighted the struggle students and parents undergo when introduced to a genuinely innovative educational model.

Responding to Tensions

The tension between implementing new ideas and preserving valuable practices was acknowledged during the first year. Instead of reacting hastily to criticism or conforming to traditional practices under pressure, the school opted to listen. Monthly meetings provided a platform to address concerns and demonstrate understanding, fostering a sense of unity within the founding team.

While the school eventually succumbed to some pressure for conformity as it rapidly expanded, the first year was characterized by holding onto this tension. Public events continually proved that students were having remarkable experiences, leading their learning at a young age. Imperfect yet profoundly satisfying, it was a year of experiments and deep learning.

Pivoting Based on Feedback

The rapid growth of the school required significant effort to believe it into existence. Team members including myself relocated across the country. Much work had to be done to build relationships, and establish trust. During this phase, negotiations around scholarship students played a crucial role for me. The commitment to inclusion was a non-negotiable aspect for the project’s goal of creating a model worthy of public school trust from my perspective. While the initial year saw some compromises, the refusal to exclude scholarship students in the second year led me to a critical pivot, and I knew that I needed to leave the project.

After my departure, the school continued to innovate and expanded to include middle and high school students. I am very proud of the video I included near the beginning of this writing, created by KLS during the school year after my departure. The video illustrates many of the design experiments that we were so proud of in the founding of KLS, from teacher ownership, mixed age learning and the power of responsibility and leadership and primary school as a true community of respected stakeholders working together to achieve success for students and growth for teachers and the school community as a whole.

References:

Wired Magzgine Oct. 2015 The Tech Elite’s Quest to Reinvent School in Its Own Image: The guy behind an online learning juggernaut has started a new school in Silicon Valley. Salman Khan is trying to reinvent the classroom. Again.

Education Next, Kapoor, Malinia June 2015 A Day at the Khan Lab School: Inquiry and self-direction guide student learning

YouTube, KLS channel 2016 Introducing Khan Academy: Video